Which is Better: Phonemic Awareness With or Without Print?

This blog post emphasizes the significance of phonemic awareness and phonics in literacy instruction, highlighting that both are crucial for reading development. In addition, it delves into the ongoing debate surrounding how to teach phonemic awareness, specifically the question of whether it should be taught exclusively with letters. Keep reading to discover more about effective phonemic awareness instruction.

Table of Contents

- Understanding the Science of Reading

- The Difference Between Phonemic Awareness, Phonological Awareness, and Phonics

- The Debate Over Teaching Phonemic Awareness With or Without Print

- The Importance of Phonological and Phonemic Awareness Instruction in Young Children

- Phonemic Awareness in Older Learners

- Balancing Phonemic Awareness with Other Literacy Components

- The Importance of Phonemic Awareness Instruction

- 6 Takeaways: Which is Better: Phonemic Awareness With or Without Print?

Free Webinar: To learn more about teaching phonemic awareness with or without print, watch our latest webinar- Phonemic Awareness: In the Dark? Or With Print?

Understanding the Science of Reading

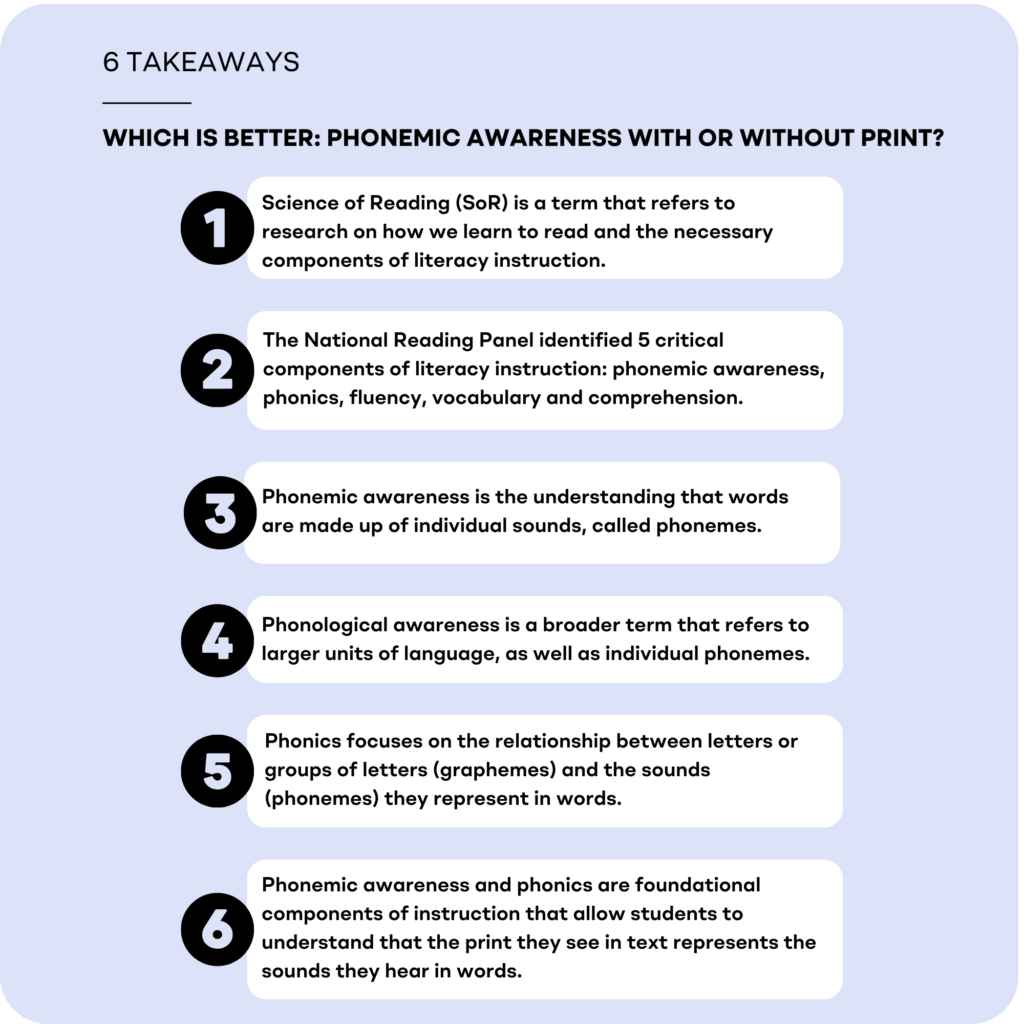

Science of Reading (SoR) is a term that has been getting a lot of attention over the past few years. While the research that SoR refers to has been around for over three decades, it is new to many educators, districts, and states. The Science of Reading (SoR) is considered a “settled science,”; meaning that we have a plethora of research that identifies how we learn to read and also identifies the necessary components of literacy instruction.

In 2000, The National Reading Panel (NRP) identified 5 critical components of literacy instruction: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. While educators and researchers agree these 5 components are critical to literacy instruction, there has not been complete agreement on how these components should be taught. While we hear “settled science” in the SoR world, there are many debates still going strong within and outside of the SoR community. Should phonemic awareness only be taught with letters? Should we spend more time building background knowledge rather than teaching comprehension strategies? Let’s delve into the initial argument: Should phonemic awareness solely rely on letters for instruction?

FREE eBook: 5 Steps to Improving Literacy Instruction in Your Classrooms– Despite research showing that most children have the capacity to read, we still see literacy scores in decline. This free eBook explores the body of research on how children learn to read and provides 5 easy first steps coaches and administrators can take to improve literacy instruction in their schools and district.

The Difference Between Phonemic Awareness, Phonological Awareness, and Phonics

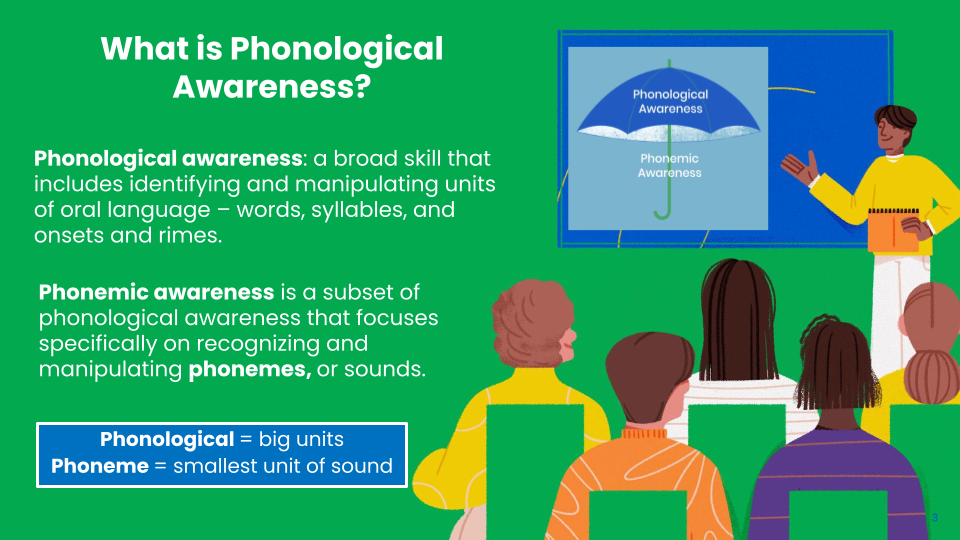

Should phonemic awareness only be taught with letters? To answer this question, it is important to understand the difference between 3 PH terms that are often confused.

- Phonological awareness is a broader term that refers to larger units of language, as well as individual phonemes. For example, we can ask students to blend the syllables nap-kin, into the word napkin. Working with larger units of language is a simpler task than working with phonemes. Blending nap-kin into the word napkin is easier than blending the phonemes /n/-/a/-/p/ into the word nap.

- Phonemic awareness refers to the understanding that words are made up of individual sounds called phonemes. While it is natural to learn to talk, it is not natural to hear the individual sounds in words because we do not /s/-/p/-/ea/-/k/ in phonemes. As we speak, the phonemes are co-articulated. Phonemic awareness needs to be explicitly taught to allow students to hear and work with the individual sounds in words.

- Phonics focuses on the relationship between letters or groups of letters (graphemes) and the sounds (phonemes) they represent in words. Phonological and phonemic awareness are both oral and auditory skills. Instruction focuses on isolating, blending, segmenting, and manipulating parts or sounds in words. These oral and auditory skills are different from another PH term, phonics. It is important to note that phonemic awareness and phonics enjoy a reciprocal relationship.

“Reading and writing present a cognitive hurdle that speaking and listening do not…there is nothing in the child’s normal experience with spoken language that necessarily acquaints him with the fact that words have an internal structure…Yet it is precisely this fact that must be understood if the alphabet is to make sense, and if its advantages are to be properly exploited.”

(Alvin Liberman, 1988)

Blog Post: You can read more about phonemic awareness and phonics in this blog post: Phonemic Awareness vs. Phonics

The Debate Over Teaching Phonemic Awareness With or Without Print

Phonemic awareness and phonics are foundational components of instruction that allow students to “crack the code” or understand that the print they see in text represents the sounds they hear in words. While there is agreement that both phonemic awareness and phonics are critical components of instruction, it is not always agreed upon on how the instruction should take place.

Some educators believe that phonemic awareness should be taught with print. The idea is that students learn the skills of isolating, blending, segmenting, and manipulating as they see print, allowing them to orthographically map the words. While this is the ultimate goal, we must remember that there are steps involved in becoming an automatic decoder of print.

Phonemic awareness is the understanding that words are made up of sounds. We can hear 44 sounds in the English language, and there are over 200 ways to bring those sounds into print. The English language is not a transparent orthography. Additionally, children can hear and work with the sounds they hear in words, even if they don’t yet know all of the letters that represent the sounds.

For example, we can say to students, “What is the first sound you hear in the word map?” Students can respond with the sound /m/, even if they do not yet know that the letter M represents the sound /m/. Building a strong foundation in phonemic awareness and encouraging students to tune in to the internal structure of language will allow for them to make more sense of how print works.

“Phonemic awareness training provides the foundation on which phonics instruction is built. Thus, children need solid phonemic awareness training for phonics instruction to be effective.”

Blevins, 42

Free Webinar: To learn more about teaching phonemic awareness with or without print, watch our latest webinar- Phonemic Awareness: In the Dark? Or With Print?

The Importance of Phonological and Phonemic Awareness Instruction in Young Children

Phonological and phonemic awareness instruction should be part of Pre-K, kindergarten, and first grade classrooms. All students need access to these critical skills, and research shows that early training of Phonological Awareness in kindergarten and first grade prevents many reading difficulties from happening. (David Kilpatrick). Additionally, in 2009 the National Early Literacy Panel identified six variables that predicted reading success better than IQ or socioeconomic status. One of these variables is phonological awareness.

As we consider this research, it is important to note that phonemic awareness training is a means to an end. With younger learners, such as Pre-K or kindergarten students, beginning with Phonological awareness instruction allows them to build an understanding of blending, segmenting, and manipulating with larger units of language. As mentioned earlier, it is easier to hear and work with larger units of language versus individual phonemes.

However, the goal is that students would begin to work with individual phonemes as soon as possible, as this is where the transfer to print occurs. Phonics instruction is much more complex, as we ask students to recognize the many different ways we can represent sounds with print.

“For those of us who already know how to read and write, this realization seems very basic, almost transparent. Nevertheless, research shows that the very notion that spoken language is made up of sequences of these little sounds does not come naturally or easily to human beings.”

Tankersley, 2003

For example, we can isolate the final sound /s/ in the words miss and nice. While the final sound in both words is /s/ we use different graphemes to represent the /s/ sound. As we work with younger learners, we do not want to hold them back from working with the sounds of words because they do not follow the same spelling pattern. This is the importance of building phonological and phonemic awareness. Students have the opportunity to become proficient with isolating, blending, segmenting, and manipulating phonemes without the cognitive load of the many different spellings for the sounds.

Watch the clip below to see an example of how our younger learners can begin to work with sounds first before attaching those more complex spelling patterns to print.

In our primary classrooms, phonemic awareness instruction should be just about 8-12 minutes, acting as an oral and auditory warm-up to phonics instruction. This warm-up allows for students to hear and work with the sounds in words and then bridge their learning into phonics instruction.

Download a FREE Digital Sample: Bridge to Reading, our new foundational skills curriculum, brings together explicit phonics instruction with Heggerty phonemic awareness lessons for a comprehensive approach to early literacy instruction that’s easy to implement (and easy to love!)

Phonemic Awareness in Older Learners

Once students have the ability to hear and work with sounds in words, phonemic awareness tasks should be taught with the print. As stated earlier, phonemic awareness and phonics enjoy a reciprocal relationship. The skill of blending phonemes orally (phonemic awareness) transfers to print as students decode or read words. As we segment a word into phonemes, it transfers to encoding or spelling as we work with print.

For example, we ask students to segment the word clap into the sounds /k/-/l/-/a/-/p/ during phonemic awareness. As they map sounds to print, students will need to identify which grapheme to use to represent the sound /k/. We can use the graphemes: c, k, ck, ch, or que to represent the /k/ sound in a word. This is an example of how phonics is more complex than phonemic awareness and why phonics also needs to be explicitly taught. While it is typically recommended that phonemic awareness be taught with print after first grade, there are times when older learners benefit from explicit instruction in phonemic awareness.

Watch the clip below to see an example of how I would use phonemic awareness as an oral warm-up with my students AND follow up with explicit instruction on how the sounds connect to print.

If students did not receive explicit instruction in phonemic awareness in kindergarten and first grade, they might still be lacking the foundational skills of phonemic awareness. Research shows that the lack of phonemic awareness is the most powerful determinant of the likelihood of failure to read. (Adams, 1990) Research also shows that older, struggling readers almost always have difficulties in phoneme awareness training that were never addressed. (D. Kilpatrick, Equipped).

When I served as a Reading Specialist for grades 3-5, I found that many of my students that needed support in decoding had the tendency to guess at words rather than attempt to blend sounds together or manipulate sounds to make new words. For example, a student might read the word “spot” at “stop” because, visually, they look a lot alike. This strategy of guessing was a habit they had learned early on, and it was not an easy habit to break! Many words look alike, and I knew it was important for my students to attend to each phoneme or sound in words.

When working with students that need decoding support, it is important to remember that phonological awareness difficulties represent the most common source of word-level reading difficulties.

Hulme, Bowyer-Crane, Carroll, Duff, & Snowling, 2012; Melby-Lervag, Hulme, & Halaas Lyster, 2012; Vellutino et al., 2004

Explicit phonemic awareness instruction allows our students to build proficiency in hearing and working with sounds so the cognitive load can be applied to the patterns of print. It also takes away the “crutch” of trying to read words as whole units or guess at visually similar words. If a student cannot blend the sounds /k/-/l/-/a/-/p/ into the word clap through the air, then they are not applying decoding strategies to print. If the student reads the word clap, they have memorized the word as a whole unit, and it is not orthographically mapped. Phonemic awareness instruction can be powerful in breaking these poor reading habits.

Blog Post: You can read more about phonemic awareness with older learners in this blog post: Phonemic Awareness in Older Learners

Balancing Phonemic Awareness with Other Literacy Components

It is important to note that phonemic awareness is just one component of literacy instruction. For older learners, it is recommended to begin at the phoneme level rather than the phonological level. Less time should be devoted to phonemic awareness in grades 2 and beyond. Typically a 5-minute oral and auditory warm-up will allow for students to engage in the skills of blending, segmenting, and manipulating phonemes. Word reading interventions were found to have highly effective outcomes when they included: intensive phonemic awareness training, phonic decoding training, and opportunities for connected text reading.

The Importance of Phonemic Awareness Instruction

As we consider the many demands we have as educators, another challenge should not be sifting through debates and interpretations of science that are already considered settled. Phonemic awareness, without question, is a skill that is required to become an automatic decoder of print. If you are teaching young children, it should be part of your Tier 1 instruction. If you have older learners that still need support with decoding, assess their phonemic awareness. If they lack these foundational skills, spending five minutes as a warm-up to working with print will be powerful and impactful.

Resources:

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Tankersley, K. (2003). The Threads of Reading: Strategies for Literacy Development. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Kilpatrick, D. (2019). Equipped for reading success: A comprehensive, step-by-step program for developing phonemic awareness and fluent word recognition. John Wiley & Sons.

Adams, M. J. (1994). Beginning to Read: Thinking and Learning About Print. MIT Press.

This article was SO impactful. I am a reaching coach for Collier County Public Schools and I specialize in grades K-2. Most of my students are English Language Learners I have often gone back and forth (with my Masters Degree in TESOL) if teaching PA was impactful for them, due to their lack of vocabulary. (example: sound, beginning, middle, end) After reading this article, I think that is is imperative to teach PA (even if it is jut the five minute warm up) and then use phonics as the bridge to that foundation to connect the phonemes to graphemes). Thank you for these articles!

Thank you for sharing! Connecting phonological awareness to phonics is essential for English Language Learners.Your dedication to your students’ learning and growth is commendable. Keep up the excellent work!